|

|

Current Issue

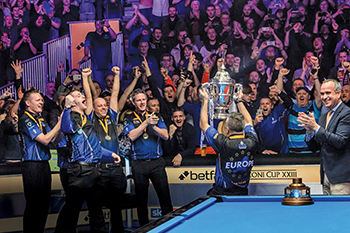

Mosconi Magic

As the Mosconi Cup turns 25, players and promoters look back at the events that have shaped pool's biggest spectacle.

By Keith Paradise

Steve Davis' hands were beginning to shake as he made his way to the Brunswick pool table in the center of the room at London's York Hall.

This was the same Steve Davis that had already collected six world snooker titles and was one of the most successful and wealthy sportsmen in the United Kingdom.

But this was American 9-ball, and facing Earl Strickland with the Europeans one match away from winning the 2002 Mosconi Cup, Davis had battled to a 4-4 tie in the race-to-five format. Strickland appeared on his way to clinching the match, but shockingly left himself a difficult angle for the 6 ball. Even more surprising, the usually clutch American missed the 6, leaving it hanging in the corner pocket.

Three balls. That's all that separated Davis and his European teammates from victory they had believed all week they were good enough to capture. Three balls separated them from ending a six-year losing streak and avenging an embarrassingly lopsided loss the year before.

The snooker legend clicked the 6 ball into the corner pocket, then cut the 8 ball into the same hole, drifting the cue ball up for perfect position on the game, match and Cup-winning 9 ball. As the crowd of 800 cheered each shot with added anticipation, the American team looked on. Davis potted the game-winner and was immediately mobbed by his five teammates. The six Europeans jumped up and down screaming while the fans roared like they'd just seen a knockout in a championship prize fight.

Juxtaposed on the opposite side of the pool table was Strickland, setting up the 6 ball shot and taking another crack.

“If I look back on my career, I've had wonderful success in snooker, but that moment is one of my finest memories,” Davis said. “Me and my five teammates huddled in the room. Without the Mosconi Cup, I never have that moment.”

Without the Mosconi Cup, the sport of pool wouldn't have many things. Originally created by promoter Barry Hearn as a televised exhibition to promote American pool in snooker-laden Britain, the event has morphed into the centerpiece of the pocket billiards calendar. Professionals from the United States and Europe battle throughout the year for a spot on the teams and fans can't wait to see it, whether in person or broadcast live. And when the event reaches its conclusion, it remains the focal point of social media and internet message boards for the following 11 months.

“The event has developed a following,” said Jerry Forsyth, who has been covering and broadcasting the event for almost 20 years. “It's a happening. People want to be there. The ultimate fan experience is the Mosconi Cup.”

Even before he became one of the preeminent producers of cue sports events, Hearn and pool frequently crossed paths. Some of his earliest television events involved professional snooker and Hearn's first office for his Matchroom production company was underneath a billiards hall near London. The early 1990s were an interesting time for the sports television programming business in England. The boom of cable television stations which swept across the United States in the 1980s was reaching the U.K. a decade later, and Hearn sensed early on that these new channels would need content. After producing the European Pool Masters in 1993, he was looking for new ways to produce and also promote pool.

One sports program which was growing in popularity at that time in Europe and the United States was professional golf's Ryder Cup. Originally designed as a friendly biannual contest between the best American and United Kingdom golfers, the Americans had dominated the event from the 1940s through the 1970s. When the format was changed to include all European golfers in 1979, the pendulum began to swing. Europe won the cup for the first time in 16 years in 1985 and retained the trophy for three straight events. The Americans fought back in 1991, gutting out a 14 ½ to 13 ½ victory in Kiawah Island, S.C. — an event now referred to as the “War by the Shore.”

One of those paying close attention to the growing intensity of the Ryder Cup was Hearn, who pitched a Ryder Cup-style event to the executives at Sky Sports. A team of European pool players challenging a squad from the United States at their own game — 9-ball.

“I copy a lot of ideas,” Hearn admitted. “And with the United States versus Europe we want to spank the Yanks and we know the Yanks want to kill us.”

“It's a concept that sells in any sport,” said Luke Riches, commercial director for Matchroom. “I think you could have tiddly winks and it would work. It's an easy thing for fans to grasp and get behind.”

Just one problem: Although the U.S. was still riding the wave of the billiards boom created by “The Color of Money” — with an established professional tour and poolrooms flourishing throughout the nation — American pool was basically invisible in Great Britain. The cue sports of choice at that time were snooker and English 8-ball, which is primarily played in pubs on smaller tables. There was a professional tour in Europe, but it wasn't nearly as lucrative or publicized as the U.S. tour, with many of the top players eventually migrating to the U.S. for events with bigger purses.

“Nobody knew 9-ball in the U.K.,” Davis said. “But since it was a fast and furious attacking game, this was a selling point. It was a real leap of faith to sell to the public.”

“They knew a few English 8-ball and snooker players, but when it came to American pool, no one was known,” said Germany's Ralf Souquet, who was in the first Mosconi Cup event and has played on 17 European teams.

“Before Barry did this, no one played American pool,” said Darren Appleton. “In the U.K., English pool is a lot more popular than U.S. pool.”

Hearn compiled the first European team with two of the top German professionals, Souquet and Oliver Ortmann, but also realized he would need brand names early on to generate eyeballs. He turned to a few of his old snooker legends — stars like Davis, Alex Higgins and Jimmy White. Although many of the players hadn't even played American pool, Hearn knew having known commodities participating would be key drawing interest.

“When you start something you have to make a splash,” Hearn said. “They didn't understand 9-ball pool and I wanted pool to be loud and brash and in-your-face. We had a small window of a few years to get broadcasters to buy into the concept and to do that, I needed famous people.”

Matchroom lobbied to bring the cream of the American pool crop to the Mosconi Cup, but then Pro Billiards Tour czar Don Mackey demanded large appearance fees for his players. (The PBT pros agreed to compete beginning in 1997.) So Hearn launched the Mosconi Cup with a mash-up of non-PBT professionals like Mark Wilson and Bobby Hunter, artistic pool competitors like Paul Gerni and Mike Massey, and living legends like Dallas West and Lou Butera. Wilson arrived for the first event with no idea what Hearn was angling for but knew it was an opportunity to travel as well as compete.

“We had no idea what the Mosconi Cup was. We just thought it was another big tournament,” Wilson said. “Plus, it was in London and I had never been to London.”

Easily forgotten is the fact the first event was coed, with Jeanette Lee and Vivian Villarreal playing for the U.S. and Germany's Franziska Stark teaming up with Allison Fisher — who at that point was still strictly a snooker player and had only tried pool once at the 1991 Munich Masters.

“We were just pocketing balls. We really didn't know the nuances of the game,” Fisher said.

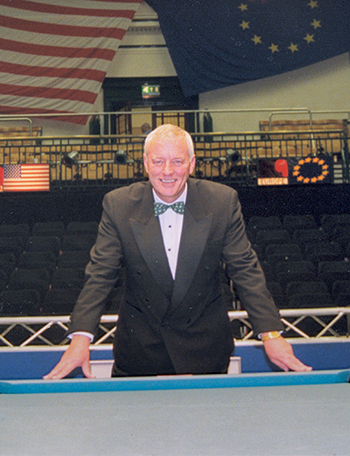

Hearn, here at York Hall in 1998, liked 9-ball because it was “loud and brash.”

Situated in the northeast corner of the London suburb of Romford, Roller Bowl wasn't the biggest or flashiest venue for the first event, but it did have two attributes which made the facility ideal. The 34-lane bowling center had an available room that could fit the event, and it was less than a mile from the Matchroom corporate offices. Decorated with an eight-foot high illuminated Statue of Liberty replica, the very first Mosconi Cup match in history got underway on December 15, 1994, with Europe's Tom Storm (Sweden) facing Hunter. There may have been 150 people in the room. Organizers were so desperate to have a crowd to help create that “splash” Hearn so wanted that they were not only giving away tickets but practically begging people to come.

“They really didn't know what they were watching,” Davis said. “A few were just out for a night of drinking.”

Most of the crowd who did show up didn't know the rules of 9-ball any more than they knew the zip code of Cleveland. To educate the public, a two-page rule book was included on the programs and broadcasters frequently referenced them during the telecast.

“I was always encouraged to remind people of the colors of the balls, so they knew which ball was which number,” said Jim Wych, who has been broadcasting the event since its inception. It's a gig that the former Canadian snooker professional literally got by being in the right place at the right time. He had been announcing snooker and English 8-ball for Matchroom when they created the event. Since American pool was involved, they figured Canada was close enough.

“I became a commentator by default,” he said. “I had a North American accent and they didn't have anyone else.”

Playing a best-two-out-of-three set format similar to tennis in singles and doubles, the United States won the first Mosconi Cup 16-12 — with Wilson pocketing the Cup-clinching 9 ball. Each player on both teams received $3,000.

The following year the event shifted to Basildon's Festival Hall, with a few tweaks to the format and the roster — most notably women were left off the teams this time. Joining the European squad would be the snooker trio of Jimmy White, Davis and two-time world champion Higgins. The event was as much a tribute to the aging legend as a billiards contest — with a brief documentary of his career broadcast during the event. The 46-year-old was to snooker what John Daly was to golf. He was brash, he was controversial, he was unpredictable and the home crowd adored him.

“He was fueled by alcohol a lot of the times but he didn't get nasty,” said Davis. “He was quite the character. I always thought he was like the Tasmanian Devil because he left this trail of devastation wherever he went. It was fun to watch the American players have to deal with this character.”

Higgins was even able to pull off a victory, teaming with White to defeat Massey and Hunter in doubles play. The point would prove to be crucial as the two teams ended the four-day event tied at 15 matches each, necessitating a one-match playoff which was won by Davis 4-2 against the 58-year-old Butera.

“It was heartwarming,” said Wilson. “If you were going to lose a Mosconi Cup, that was okay. It was fun.”

The following year, the Matchroom assembled a team loaded with some of the game's top American professionals — including C.J. Wiley, Allen Hopkins and a 34-year-old Strickland.

With Lady Liberty looking on, the Mosconi Cup launched as a co-ed team tournament at a Romford, England, bowling alley in 1994.

If the Mosconi Cup was a loaf of bread that Hearn was baking, his decision to move the 1997 event to London's York Hall was the addition of yeast. Located in the Bethnal Green section of East London, the dingy old hall is one of the most famous boxing arenas in town and had stadium seating with a balcony that made competitors feel like spectators were right on top of them. If Hearn wanted brash and in-your-face, he needed a brash and in-your-face venue.

“To take the Mosconi Cup here was a gamble,” Hearn said. “It's a historic venue that fills up for almost anything. I needed something that told me I'm on the right track, that the light at the end of the tunnel wasn’t an oncoming train. Because if this doesn't work, even I'm saying we're in trouble.”

Not only did the place fill up (again, thanks to free tickets), it was at York Hall that the Mosconi Cup's crowd began to spread its wings and the event grew from exhibition to competition. Fueled by the traditional rivalry between Europe and the U.S., as well as an open bar, the crowd grew bold, boisterous and loud. With a local man named Henry leading cheers and songs, the atmosphere was equal parts boxing and soccer. European players were cheered and serenaded, while American players many times were only cheered when they missed a shot. It was a crowd like pocket billiards had never seen before.

“No one can prepare you for that crowd until you experience it because that's not how we experience pool in America,” said Michael Coltrain, a two-time U.S. team member. “It's kind of like [Duke University's famed] Cameron Indoor Stadium but smaller. The sound bounces off the ceiling. It felt for the first time like I was in enemy territory.”

“That was different,” said Jeremy Jones, who has played on seven Mosconi Cup teams and is cocaptain of this year's team. “That didn't bother me. That more or less is what I thought an English pool hall would be like after a few beers.”

The tension created at the Cup's new home was enough to emotionally unnerve Italy's Fabio Petroni. Playing in front of a packed house on live television was too much pressure for the Italian to handle, with Petroni moved to tears a few times during the week. He was able to scratch out a doubles victory with Davis, but was winless in singles competition.

“I was under pressure too much,” Petroni said. “I feel like it was my moment and I wasn't in the real world. For a while, my mind was going on a trip.”

Coltrain knows all too well what its like not to be able to perform to your capabilities in the event, although his struggles were of a much different variety.

As one of the top four players on the Camel Pro Billiards Tour in 1999, Coltrain was an automatic qualifier for that year's U.S. team. He made the most of his first appearance, bringing his father and girlfriend to London for the experience, then executing a jump shot without a jump cue to run out and help secure a 5-4 doubles match victory with Jones on the event's first day. The broadcasters were so impressed that they interviewed him after the match then had him attempt to recreate the shot the next day for the cameras.

“It was a moment I'll never forget. I became a celebrity in U.S. pool for like a day,” Coltrain said.

Over the next 12 months Coltrain developed an occasional shake in his arm that was diminishing his play. As luck — or possibly bad luck — would have it, this was the same year that the tour went under, meaning there weren't any tour rankings to help select an American squad. Instead, Matchroom simply invited back the previous year's squad.

“No way would I have earned a spot had there been a tour,” Coltrain said.

The doubles pairing of Coltrain and Jones lost its first two doubles matches. Coltrain battled back, winning a doubles match with Corey Deuel against Souquet and Thomas Engert then taking advantage of some unforced errors to defeat Marcus Chamat in singles, 5-3.

Coltrain's lowest point of the week and of his career would come on the last day of competition. Facing Steve Davis, he failed to capitalize on numerous open tables and was shutout, 5-0. Matchroom forbade players from leaving the venue during competition, but with the grim reality that his pool playing days might be over, Coltrain needed to get out of York Hall. He stored his cue, put on his coat and walked a few blocks down the street where he found a pub. When he entered, still dressed in his team U.S.A. attire, he saw three televisions — and all of them were tuned in to the event. When a patron recognized Coltrain, he bought him a drink and offered some encouraging words with a pat on the back.

“He was very nice. Just told me to keep my head up and kind of gave me a pep talk,” Coltrain said. “I walked in with my head between my legs. I was as sad as you could get.”

When Coltrain returned home, he was diagnosed with Focal Task Dystonia, a neurological movement disorder that interferes with particular tasks and is characterized by involuntary muscle contractions, tremors and other uncontrolled movements.

Despite Coltrain's struggles, the United States still won the Cup for a fifth consecutive year, 12-9. Although usually a third of its roster was more proficient at snooker, the Europeans battled the Americans but struggled to finish them off. Making matters more difficult for the Europeans was the fact that the U.S. was bringing over future Billiard Congress of America Hall of Fame players who were at peak performance abilities, like Strickland and Johnny Archer as well as future Hall of Famers like Jim Rempe who were aging but could still compete at the highest level.

“At that point, we were good but I didn't think we were at their level yet except for Mika [Immonen] and Ralf,” said Marcus Chamat, who played on six European Cup teams and has now captained for the past three years. “The Americans at that time, they were still at the prime of their careers.”

Just one year after a demoralizing 12-1 defeat, Team Europe earned a statement victory over the U.S. in 2002, setting the tone for the years to follow.

Despite the losing streak, the Euros entered the 2001 Mosconi Cup with a confidence that the streak was about to come to an end. It was possibly the strongest team they'd put together, with Souquet, Immonen, Davis and rookies Chamat and Holland's Niels Feijen, who had finished second to Efren Reyes at that year's Toyko 9-ball event and came in fifth at the U.S. Open.

“We had the dream team,” said Chamat.

When Feijen and Immonen gave the Europeans a quick 1-0 with a 5-3 victory against Archer and Varner, it appeared the dream might become a reality.

Then the wheels feel off. And the engine seized up. And the rest of the car caught fire.

Europe went on to lose every remaining match, with the 12-1 annihilation ranking as the biggest margin of victory in the event’s history. It was one of only two times in the 24-year history of the event that play was completed in three days instead of the scheduled four.

“I don't think I've ever seen anything like it,” said Immonen. “I don't think we played that bad, it's just that weird things happened. We would get a bad roll here or there. It was a combination of so many bizarre events.”

“We were expected to give them a run for their money,” said Chamat. “The result was a big disappointment.”

The following year Europeans were out to prove that previous year was an aberration. From the moment the team congregated in London they bonded. Ortmann took the reins as playing captain and worked to mold the group into a team by spending free time and practicing together. They were confident but also loose, thanks to Ortmann playing the song “Kids” from the American Teen soundtrack on his phone to keep his teammates light.

“We went out at night and ate together. We cheered each ball,” Davis said. “The only thing we didn't do was sleep together.”

“Instead of stressing too much, we were able to trust our skills and pull together as a team,” Immonen said.

The Europeans jumped out to a 5-1 lead midway through the second day of competition. The Americans rallied, winning five of six to even the score at 6-6. In previous years this would be the time that the Americans would surge ahead and coast to a victory. This time, however, the Europeans won four out of six singles matches to carry a 10-8 lead into the final session of play.

Lubricated by the home team leading, along with a couple of pints, the pro-Europe crowd was electrified and anticipating victory. When Chamat entered the top of the arena to walk down for player introductions his feet never touched the ground as the fans carried him down the steps. Chamat responded by pushing Europe onto the hill with a resounding 5-2 victory over Varner. The United States pulled to within 11-9 when Charlie Williams defeated Souquet and, with the usually solid Strickland at the table, it looked like the lead would be trimmed to one.

Until, of course, Strickland left that fatal 6 ball dangling in the jaws of the corner.

“To beat that team, it was like we climbed Mount Everest,” Davis said.

“We realized that the American team wasn't unbeatable anymore, and I guess that had them thinking too,” said Ortmann. “We were no longer the underdogs, and after a few years, the Europeans became stronger and stronger as well.”

Van Boening bagged the clincher for Team USA in 2009 in Las Vegas, marking the last time the Americans tasted victory in the Mosconi Cup.

Europe's victory proved to be a pivotal moment in Mosconi Cup history. It ended a seven-year span of American domination and demonstrated that the Europeans could beat the United States at its own game, even with many of the American stars in the prime of their careers. The upset not only gave the Europeans the confidence they needed as competitors but it also gave Matchroom proof that a truly dramatic and competitive event had finally taken root.

The following year the competition would be played on U.S. soil at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, beginning a new pattern of alternating continents. Over time, the free spectator entry vanished, as fans were not only willing to purchase tickets but were many times snatching them up immediately after being made available.

The final sign that the Mosconi Cup was walking, talking and starting to feed itself was in 2005 when the European team did not include Davis. Part of the reasoning was that the event conflicted with dates for the UK snooker championship. The other half was that a recognizable snooker star wasn't needed anymore. People were tuning in for the event itself and not the names involved.

“Steve played in this as a favor to me,” Hearn said. “The day we turned and said we don't need you anymore is the day we became proper.”

The players that audience members were tuning to watch had plenty of passion and personality to make for compelling television — maybe no one more so than Strickland.

By the time the 2000s rolled around, Strickland had established himself as a pool legend, winning five U.S. Opens, three WPA World 9-ball Championships and a World Pool Masters title. The only thing that came close to Strickland's talent at a pool table was his ability to erupt.

“Earl Strickland can make you pull your hair out but you miss him when he's not there because you're on the edge of your seat,” Hearn said. “Natural geniuses like Strickland are natural characters, even though there were a lot of times I wanted to throw him off a cliff.”

If Higgins was the Tasmanian Devil, then Strickland is Yosemite Sam — a fiery antagonist who was quick to shoot. He sparred with the fans and opposition equally, providing a running commentary through many of his matches which could alienate or annoy. In a pressure packed 2006 Cup contest in Holland, the United States trailed 8-5 when Strickland faced Engert. He led 6-3 and looked positioned to clear the 10th rack to win the race-to-seven match, but rattled the 7 ball in the jaws of the corner pocket. Furious with himself, Strickland slapped his stick against the ground and watched as the shaft splintered apart, drawing cheers and honking airhorns from the crowd.

Strickland screwed on a replacement shaft and won the match 7-4, but the two teams fought to a 12-12 tie — the only recorded tie in event history.

The very next year at the MGM Grand, Strickland spent most of the week outspoken about his displeasure with the Europeans and got into a heated running dialogue with Daryl Peach during their match on the final day of play. With the Americans trailing, 10-7, and Europe needing one more match for its first victory since 2002, the woofing became so intense that referee Michaela Tabb had to come between the two players and tell them to cool it. Strickland went on to win the match, 6-3, but the Europeans would regain the Cup, 11-8.

Despite the lopsided nature of the competition over the last decade, the Mosconi Cup had become a box-office bonanza.

“Earl started taking it personally when the U.S. started getting beat,” said Jay Helfert, who has announced the event for more than a decade and has been involved in pool for over a half-century.

“For me, when he went off like that, it was a nightmare. I couldn't handle it,” said former teammate Rodney Morris.

“Earl really started to be a cancer to the team,” said Appleton. “He started to blame everyone but himself.”

Strickland continued to give a running dialogue to fans at the 2008 event in Malta, openly complaining about how easy the Brunswick table used in competition was playing. After winning a doubles match with Johnny Archer on the first day of play, Strickland made his opinion known in the post-match interview on live television.

“What I want to do, and what I think the best players in the world should do, is go to a five-foot by 10-foot table,” Strickland said. “You want to see real pool or do you want to see guys shit on themselves?”

The announcer immediately apologized to viewers for the language.

“He was an easy mark,” said Archer. “Someone would say something and get on him but he gave his share back. It was a love-hate relationship.”

His play gave American pool fans much to love, going 15-12 overall in singles play and 24-14 in doubles competition in 14 appearances, earning the event's Most Valuable Player award three times as the U.S. won three consecutive cups after the 2002 defeat.

Strickland declined to be interviewed for this story.

“Earl was as good a shot maker as I've ever seen,” said Wych. “His antics are always in question, but that’s part of the drama.”

“I'll bet the long-standing Mosconi Cup fans miss Earl being there,” Archer said.

As the drama was gradually generated a devoted following, the event's finances, which looked as dismal as team Europe's results for the first decade, began to turn around. Hearn estimated that he personally lost $2 million total on the event in the early stages before breaking even. Although his accountants would question if he was happy with the event's fiscal performance, he was undeterred.

“You knew it could be turned around,” former Matchroom Chief Operating Officer Sharron Tokley said. “Barry Hearn never gives up on anything.”

His perseverance has literally paid off. The Mosconi Cup is now a solid draw on British TV, and although SkySports declined to release television ratings information, Hearn stated the event draws comparable to one of his medium-sized boxing promotions.

“It doesn't blow Premier football out of the water, but it draws well enough to keep getting renewed,” said Riches.

The event also continues to expand, with the competition now being broadcast live in 135 countries. Part of the reason it continues to generate an audience is the obvious storyline of country versus continent. The other factor is that Matchroom develops some of the highest quality sports shows from a production standpoint. Armed with a team of color commentators, a sideline reporter and professional sports-style graphics and social media, the display of the event is second-to-none.

“We'll never use seven or eight cameras on a show when we can use an excuse to use 10 or 11,” Hearn said. “We want to make the viewer feel like they're there.”

Oddly enough, one of the countries Hearn has struggled to penetrate with the programming is the home of Europe's opposition. Matchroom has approached ESPN in previous years about airing the event and been relegated to the network's digital app, ESPN 3. This year, American pool fans will be able to watch the competition live on Facebook, which has purchased the rights to the event. The arrangement puts the event in pretty exclusive company, with Major League Baseball also airing select games on the social media platform this past season.

“The days of the U.S. television network are over,” Hearn said. “They don't have the same capabilities in the digital age.”

The only aspect of the event that has diminished since it started has been the American team's fortunes, with the team winless for almost a decade. Captained by Dutch coach Johan Ruijsink, with strict adherence to details, drills and discipline, Team Europe won five consecutive events from 2010 to 2014. Chamat stepped in as captain in 2015 and has led the team to three convincing victories the past three years, including an 11-3 decision in 2016 and 11-4 last year.

Ask any one person connected with professional pool what's lacking on the American side and you're likely to get at least three answers back. Some feel the lack of a professional tour in America while Europeans compete on the EuroTour gives the opposition a competitive advantage. Others believe the Americans sense of unity and camaraderie is lacking compared to their adversaries. Others are even more direct.

“I think a lot of guys are looking at this as a paycheck, as a stepping stone,” Archer said, adding that he doesn’t feel many players are as engaged with their teammates' matches as they should be. “You have to really fully want him to make that ball. You actually feel for him like you would if it was you.”

“You have to be a team player and a lot of guys are not team players,” said Morris. “Not a lot of players are built for the Mosconi Cup.”

Compare that to the European side, which seems to have a limitless roster of talented players who are not only built for the team environment but also thrive in it.

“It doesn't matter who makes the team, they're on big stages month in and month out,” said Appleton. “Other than Shane [Van Boening], there is no one else doing that in America.”

The lack of competition certainly hasn't hurt attendance. If anything, it may have helped. After drawing around 1,200 in 2014 and 2015, Matchroom moved the event to Alexandra Palace for 2016, marking the first time the event's paid attendance topped 2,000. The silver anniversary clash this December is set to be the biggest yet, with 2,600 spectators expected to pack Alexandra Palace.

“The English love to see the Yanks get their asses kicked,” said Helfert. “All of the English fans are laughing and joking as they're leaving.”

Although business is good now, Matchroom executives are aware that the U.S. will need to find a way to become competitive again for the event to continue to thrive, as even the most ardent European supporter will eventually grow bored with one side dominating the other. It's a major reason Ruijsink was brought back to captain and coach the Americans the past two years and given the freedom to select the players and practice regimen.

“We do realize that it can't go on forever with one side winning every year,” said Riches. “That's a fact.”

Top |

|