|

|

Current Issue

Next Page >

|

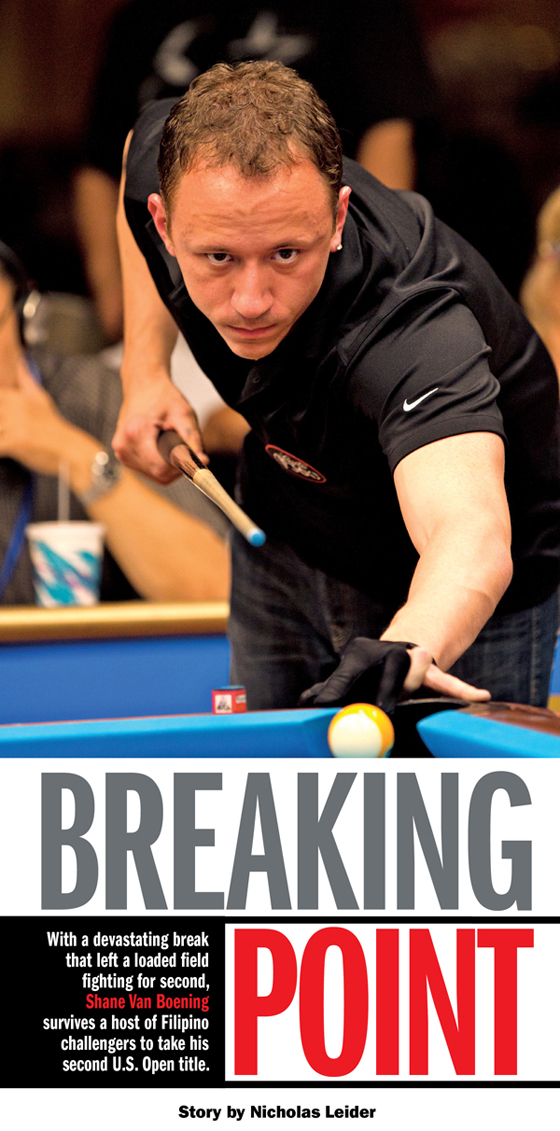

SHANE VAN Boening has never been much of a talker. So when he reflected on his dominant march to the 2012 U.S. Open 9-Ball Championship - a performance that included a break so effective it left players and spectators shaking their heads, wondering if they were watching the American drive the final nail into 9-ball's coffin - it took all of five words to sum it up.

"Everyone complains when they lose," he said.

And at this year's U.S. Open, Van Boening didn't have much to complain about. On his way through the 219-player field, he faced exactly one challenge, a hill-hill victory over Ronnie Alcano, his opponent in the 2007 final. Outside of that scare, Van Boening was in control the entire week, with his second closest margin of victory an astounding six racks - the difference in his 13-7 title-clinching set against Dennis Orcollo.

"I've played more pool in the last month than ever," he said, which is no small accomplishment for someone known to spend so much time at the table. "I was pretty well prepared for this tournament. I came here with a lot of confidence in myself, so I really didn't have to worry about who I'm playing."

Not when you have a not-so-secret weapon like Van Boening's unmatched break.

While the game's detractors have always been around, 9-ball has been under increased scrutiny in the past decade with the prevalent use of the soft break, or cut break. The idea is simple: Use as little power as possible to pocket a ball and maintain control of the cue ball. If you can consistently sink a wing ball (the ball to the left or right of the center 9 ball), a well-placed cue ball can lead to beaucoup break-and-runs.

Corey Deuel's victory at the 2001 U.S. Open remains the high point for the less-power-is-more approach. But to encourage more denture-rattling break shots, tournaments have instituted rules. One, for examle, calls for three balls to be pocketed or pass the center string in order to be legal.

But when it comes to Van Boening, there is nothing soft about his opening salvo. He drills the rack, often popping the cue ball six inches into the air after smacking into the 1 ball. Ideally, the cue ball then goes to the side rail just south of the side pocket and toward the middle of the table, well after a wing ball screamed into the corner pocket.

"I've been practicing that break for five years," Van Boening said, which proved so effective in Virginia Beach that he pocketed the wing ball on all 13 of his break shots in the final, scratching just once. "That's the way I should be breaking all the time."

Taking the soft out of the soft break, all while maintaining its efficiency, is the latest development that's sparked plenty of conversations on fixing 9-ball. For Van Boening, though, nothing about being too successful seems in need of repair.

Next Page >

Top |

|