|

|

|

| HomeAbout Billiards DigestContact UsArchiveAll About PoolEquipmentOur AdvertisersLinks |

|

Browse Features

Tips & InstructionAsk Jeanette Lee Blogs/Columns Stroke of Genius 30 Over 30 Untold Stories Pool on TV Event Calendar Power Index |

Current Issue

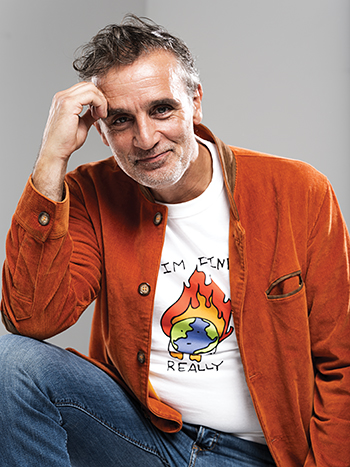

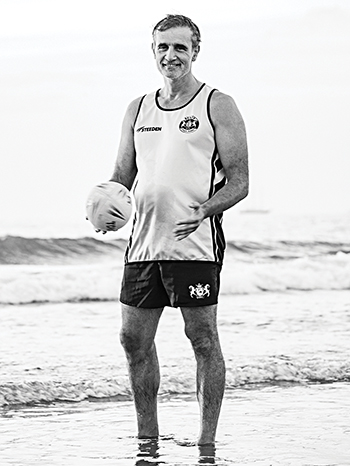

Being Alex Lely WithFrom Myers-Briggs to Wim Hof, stand-up comedy to political office, “brain machines” to sports psychology, and one-pocket to coaching, Dutchman Alex Lely is on a constant search for knowledge and enlightenment. By J.D. Dolan Photos by Rein Langeveld When he was a boy, the center of Alex Lely's world wasn't the Hague, or the Netherlands, or Europe — it was rugby. His father had been a rugby player, and the young Lely wanted to be a rugby player too. When he went to school he thought about rugby, and after school he played rugby, and in bed at night, he dreamed of rugby. “I didn't think about anything else,” he says. “I was a maniac.” At five, he became the youngest player on the Hague Rugby Club. In school, he learned easily but was distracted. One course that held his attention, though, was on billiards. The course only lasted four weeks, but it was enough to introduce him to the basics of the game. His father bought a small carom table for their home, and then later bought a small pool table. When he was 15, Lely started working as a paperboy and saved his money. That summer, he went to the Baskuul coffee shop, which had a small coin-op pool table, and, for two weeks, guilder by guilder, fed all of his savings into it. When he found out what his son had done with his savings, Lely's father grabbed the boy's pool cue, broke it over his knee, and said, “You're never going to play pool again!”  (Photo by Photo by Rein Langeveld) Now, at 49, with a solid record as a world-class pool player, a teacher, a television commentator, and the captain of the European Mosconi Cup team, Lely can laugh when he tells that story, but he still shakes his head. Lely has lots of stories, and he's able to tell them in five languages — Dutch, German, Italian, French, and English. He says he also speaks “monkey Russian,” but he's likely being modest. If not for his slight Dutch twang, and the fact that his English is too good, he could pass for an American. He sports a neat, close-cropped beard and a faded madras newsboy cap, and yet he somehow doesn't seem to be trying to look like a hipster. At six feet and 185 pounds, he's tan and fit, and his nose, which he broke twice playing rugby, gives him what a casting director might call “rugged good looks.” “The last time they tried to fix it,” he says, referring to his nose, “they took part of a bone from my rib and put it in there.” Then he adds, matter-of-factly, “It still doesn't work right.” Lely's fifteen-year history in rugby is written on his body. In addition to his twice-broken nose, he suffered broken fingers, sprained ankles, severe concussions (twice), a dislocated shoulder, and too many scrapes and bruises to count. Still, he loved the game and continued to play it through high school. When he wasn't in school or playing rugby, he liked to ride his bike to the Baskuul coffee shop, where, to the music of Clapton and Hendrix and Santana, he and his friends smoked ganja and played pinball and foosball and pool. One day, while he was playing line-up pool for drinks, one of his older friends noticed his abilities and offered to take him to a nearby pool room in Leiden with nine-foot tables. There, Lely won the equivalent of about $300 one day and then went back the next day and did the same thing. “I was hooked,” he says. He graduated from Gymnasium Haganum at 18, though he says the fact that he graduated at all was a miracle. “For the last three years I was stoned the whole day through,” he says. But it was a special school — one of the top three in the Netherlands — with special kids and special teachers. “I learned easily but I wasn't disciplined,” he says. Lely may not have learned discipline in school, but he learned it in other ways. He studied aikido techniques to improve his rugby game; he also developed an interest in yoga and tai chi. To deal with the pain from his injuries, he practiced breathing exercises, and, taking a tip from Thai kickboxers, he ate red kidney beans to reduce joint inflammation. To accelerate his learning, he used Super-study methods, and to improve his performance under pressure, he listened to self-hypnosis tapes. He even became interested in neurolinguistic programming, and traveled to Amsterdam to buy what he calls a “brain machine.” Lely was open to anything that would make him stronger mentally and physically. He says his unconventional training methods allowed him to get by on just four hours of sleep a night. “I was the skinniest player on the team,” he says, but he showed enough potential that he was offered a scholarship in England. Still, he kept racking up more injuries. That's why, at 20, he decided to quit. “I took everything from rugby and put it into pool,” Lely says.  Lely still plays the occasional game of rugby, despite years of bruises and broken bones. (Photo by Rein Langeveld) The year was 1993, and Lely watched every Accu-Stats video he could get his hands on. He studied the matches of Oliver Ortmann, Ralf Souquet, Efren Reyes, Mike Sigel, Buddy Hall, Earl Strickland, and others. Steven Verharen, one of Lely's friends from their coffee shop days, opened the Hague 5 Sportsbar, a pool room that quickly attracted some of the most dedicated players in the Netherlands, including Lely, Johan Ruijsink, and a younger guy named Niels Feijen. “We come from a small country,” Lely says. “We all knew each other. We all trained together and learned together.” “Alex was an incredible student of the game,” Feijen says. “He was also kind of a bully.” After five years of training, Lely turned professional in 1998. He won the World Pool Masters the following year, defeating Efren Reyes 9-7 in the finals, and later that year defeated Francisco Bustamante in the finals of the Eurotour German Open. These stunning early successes may have both helped and hurt the trajectory of his career. He was selected for the 1999 European Mosconi Cup team, which was captained by U.K. snooker legend Steve Davis. Lely's other teammates were Steve Knight from the U.K., Mika Immonen from Finland, and Ralf Souquet and Oliver Ortmann from Germany. They faced off against American team captain Jim Rempe, along with Johnny Archer, Kim Davenport, Earl Strickland, Michael Coltrain, and Jeremy Jones. The European team didn't fare very well, losing, 12-7, to the Americans, but Lely and Davis did manage to win their doubles match against Coltrain and Jones. This was the first and last time Lely and Jones battled each other — as players — in the Mosconi Cup. In 2000, Lely made it to the finals against Oliver Ortmann in the straight pool division of the European Pool Championships. Ortmann ran 117, and Lely responded with a 117, his first century in a straight pool match. Ortmann missed soon after, and Lely ran 29 — and missed. Ortmann ran out from there and won 150-146. Lely also made it to the finals of the World Pool Masters that year, but missed the 9 ball three times and lost 3-7 to Souquet.  Lely admits he wasn't “ready” as a coach when he captained Team Europe in the Mosconi Cup in 2007 and 2008. Lely had a fallow period for the next couple of years, and he used the time to develop himself outside of pool. “I studied political science,” he says. “I used to just automatically go to the pool room every day, and I stopped doing that.” He still trained, but because he had less time, his training became more focused. He worked on straight pool with Feijen, Nick van den Berg, and Rico Diks, and he worked on bringing structure and purpose to his game with Ruijsink. In 2002 he won the inaugural Fujairah International 8-Ball Tournament, beating Johnny Archer 13-10 in the finals. In 2004, his daughter, Josephine, was born, and things seemed to continue coming together in his life. In 2005 he won the Italian Open; he also won the European Pool Championships in both 8-ball and 9-ball divisions, and was a member of the European Mosconi Cup team. He and Feijen beat Shawn Putnam and Charlie Williams in their doubles match, but it was otherwise a poor showing for the Europeans. Lely managed to win the Netherlands Open in 2006, but the travel was getting to him. Sometimes he wouldn't have time to unpack from one trip before he set off on another one. “I was just fed up with the whole thing,” he says. In 2007, not long after the birth of his son, Zeger, he retired from the professional pool circuit. He tried his hand at politics, winning a seat on his town council to represent the Social Democrats. He liked running the meetings, but he got bored with the procedural monotony. In 2008, he captained the European Mosconi Cup team, which defeated the U.S. team 11-5. In 2009, he captained the team to a 7-11 loss. “I wasn't really ready as a coach,” Lely says. “But are you ever ‘ready' for the Mosconi Cup? I was more like a mascot.” But Lely continued to train himself and others. In 2011 he teamed up with Ruijsink to put on a training seminar called Bootcamp: Skillz&Drillz, which featured five full days of training in “technique, shot-selection, kick-shots, safeties, [and] the mental game.” The seminar focused on straight pool, which Lely considers to be one of the best games to develop a strong foundation, and also, with the help of his trusty “brain machine,” introduced the players to Neurolinguistic programming. But Ruijsink and Lely always made sure to include a few hours in the evening to relax and have fun away from the pool table. And while his focus may have been on training and coaching, Lely continued to play now and then. He competed in the 2015 Derby City Classic and finished 4th in the 9-ball division. And in 2018 he set up a camera to record himself playing straight pool and streamed the live video to Facebook. The result? A run of 308. In 2020, Lely was chosen to be the coach of the European Mosconi Cup team, with Karl Boyes as vice captain. This brought with it a fair amount of pressure. The European team had won eight of the last ten years, first with the coaching of Ruijsink, and then with the coaching of Marcus Chamat, but the U.S. team had won the last two years — with Ruijsink as the U.S. coach. “Yeah, of course I felt pressure,” Lely says, “but just like a player you keep your eyes focused on the things you need to do. It's like a constant worry — not a worry — but you're never relaxed.” Lely didn't have to square off against his old friend Ruijsink, since the Americans had chosen Jeremy Jones as their captain and Joey Gray as vice captain. But there was still another pressure that Lely — and everybody else — had to contend with: COVID-19. The American team had already lost one player, Justin Bergman, to COVID; he was replaced by Corey Deuel. “We felt like we were lucky to get everybody there,” Lely says. After their arrival, both teams had to be tested for COVID, and then they were quarantined in the hotel for four days.  Then the top Dutch player, Lely played in the Mosconi Cup and the World Pool Masters in the late '90s, winning the Masters in 1998. “Our practice facility was massive,” Boyes says, “with a dart board in there, we had table-tennis, we had fridges full of drinks, and snacks, and we had music, so it was really good.” During those stressful days, Lely had the team play singles and doubles matches, with Boyes working a time clock and Lely taking notes. He also had the players work on drills. “I think where Alex is very good is — not just Alex, I think it's the Dutch mindset, even like Johan when he was captain, he was very similar,” Boyes says. “They've got loads of drills and games they can play on a pool table, so it never becomes boring. You're not just breaking and running the table.” Lely would also work with the players one-on-one. “If somebody was looking a little despondent or down, he'd just say, ‘Let's go outside for a walk.' It was just very good man management.” The team evidently responded well to Lely's and Boyes' efforts to keep the mood upbeat. When they weren't on the pool table, they played board games and darts, and especially team ping-pong, with everybody running around the table. The last man standing was the winner. “That probably got a little bit silly,” Boyes says. “We was probably having a little too much fun.” After the first day, Lely and Boyes banned ping-pong until the serious practice was over. The U.S. team also had a ping-pong table in their practice room, but they kept theirs shoved up against a wall. “When we ran into the Americans in the hallways,” Lely says, “it felt like a little bit of a Cold War.” Perhaps one of the strangest aspects of the 2020 Mosconi Cup is that there were no fans. “It was a weird year for everyone,” Lely says. Despite the somber mood, Europe managed to win the first session 3-2, after which Lely and Boyes decided their team needed make some noise on the sidelines. “Just like you would on league night,” Boyes says, “when your team's playing on a Tuesday and no one's watching. You've got to get a bit of emotion in there. I think that was the big thing really. We managed to create a bit of an atmosphere.” It seems to have worked. Team Europe ended up beating the Americans 11-3, and celebrated afterward by playing beer pong with whiskey.  Since taking over Team Europe in 2020, Lely has gotten the better of Team USA's Jones. The 2021 Mosconi Cup was held in England again, but this time in London's Alexandra Palace. And there were fans! But COVID wasn't quite done with the pool world (or the rest of the world) just yet. The American player Earl Strickland was exposed to COVID on the flight to London and was not allowed to play in the tournament. Team captain Jeremy Jones had to step in to take his place. This year, as in the year before, team Europe got off to a slow start (with at least one serious misstep, when Eklent Kaci shot out of turn), but were able to tie the first session 2-2. They were down 3-5 in the second session, but strung together four racks in the last match to finish the day at 4-5. “That night, I couldn't sleep,” Lely says. “I woke up at five and then I got all the guys to my room at nine. I gave them a speech, I made a mistake, we made a mistake. “We had been lucky enough to win that last match on day 2. It could have been 6-3. I told them, ‘it's basically between you five,' and then Karl and I left the room, and we had them talking to each other.” After that, Lely says, “we made sure to heighten the intensity and the discipline in our practice sessions and when people were at the table.” The pep talk worked. That day, Team Europe won all five matches, a crushing performance marred only by the last game. Jones was playing David Alcaide and had the game and match nearly at hand when he asked the ref to clean the cue ball with only 12 seconds left on the shot clock. The result was a time foul that honestly seemed to make everybody on both teams a little sick. Alcaide cleaned up the remaining balls to bring the score to 9-5. “From there we felt like we could win the whole thing,” Lely says. The team may have become more disciplined, but, Lely says, “We were still having a lot of fun. Filler and his wife, Pia, had a big room, where the team played Jenga and poker and all kinds of games.” On Day Four, team Europe won the 2022 Mosconi Cup, 11-6, but Lely isn't one to dwell on the victory. “I'm looking to do better this year,” he says. “Get everyone sharper right from the get-go, get them fired up, get everyone intense enough. We were favorites in 2018 and 2019 and we lost on both occasions. We have to keep that memory fresh.” “You suck!” is one of many similar message-board comments Lely got for his recent foray into commentating on kickboxing matches. When he read the brutal fan messages, he decided to start training in kickboxing himself — not to beat up the fans (maybe), but to make himself a better and more knowledgable commentator. On a recent trip to Chicago, Lely sipped at a breakfast smoothie and talked about his morning swims in Lake Michigan. He talked about Myers-Briggs personality types and how he became a Myers-Briggs coach. He talked about being an adherent of Wim Hof, who touts the benefits of ice baths for heightened oxygen levels. He talked about playing one-pocket with Ike Runnels at Red Shoes Billiards. He talked about the Israeli philosopher Yuval Noah Harari, the Lebanese-American mathematical statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb, and the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung. He talked about becoming, for a while, a vegan. He talked about running corporate seminars. He talked about the Lollapalooza music festival, which he would be attending in a few days with his daughter and his Italian cousin, Giacomo Liberotti, a rocket scientist. He talked about sports psychology. He talked about becoming a Sight-Right coach. He talked about taking a course in stand-up comedy. “That was,” he says, “the scariest thing I've ever done.” And, of course, he talked about training in pool, and on this Lely's beliefs run deep. For him, training isn't just about pool — it's a way of life, and a way to help others help themselves. “The key to better performance in competition is better practice,” he says. “Finding ways to practice with more pressure. What you do a lot you become good at.” “He's a good trainer,” says Allison Fisher, whom Lely worked with on a recent U.S. trip. “A trainer is a much more involved person in your well-being and betterment. He's a man's man. The people respect him, the players.” Jayson Shaw has a similar take. “He's the best coach I've ever worked with. His work ethic is amazing. He takes no short cuts. He makes you work hard and pushes you to be the best you can be. He just has a great way of making you feel at ease and helping you when feeling little bit off. He works all year around, not just at the Mosconi Cup.” But of all of his interests and pursuits, Lely still loves to play pool, and in particular he loves to be in action. He says he's watched every one pocket match on YouTube. “I can say ‘trap' in 10 languages,” he says, and smiles. Still, sometimes, when he goes to bed at night, he dreams of rugby.

|

Since 1978, Billiards Digest magazine has been the pool world’s best source for news, tournament coverage, player profiles, bold editorials, and advice on how to play pool. Our instructors include superstars Nick Varner and Jeanette Lee. Every issue features the pool accessories and equipment you love — pool cues, pool tables, instruction aids and more. Columnists Mike Shamos and R.A. Dyer examine legends like Willie Mosconi and Minnesota Fats, and dig deep into the histories of pool games like 8-ball, 9-ball and straight pool.

Copyright © 1997 - 2025 Billiards Digest

All Rights Reserved

Luby Publishing, Inc.

310 Busse Highway PBM #319 | Park Ridge, IL 60068

Phone: 312-341-1110 | Fax: 312-341-1469