|

|

Current Issue

Next Page >

The Snail's Tale

Dominant despite a maddeningly deliberate style, Frank Taberski ruled billiards in the years before the rise of Ralph Greenleaf

Story by R.A. Dyer

|

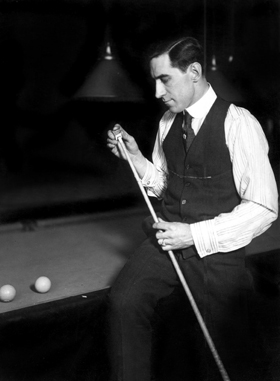

| Taberski won 10 challenge matches during his 16-month reign as champion. (Photos courtesy the Billiard Archive) |

RALPH GREENLEAF was dynamic and brash, tempestuous and ill-tempered. His stroke was liquid smoothness, like fine and strong whisky - beautiful to behold, difficult to master. Greenleaf shot quickly. He was a risk-taker.

Frank Taberski preferred safety play to break shots. He avoided risks, opting instead for a slow-down game that annoyed opponents and spectators alike. If Greenleaf was whiskey then Frank Taberski was cold milk. Or molasses.

Both were fine players, but history remembers Greenleaf as the greatest of the era. And yet for a brief period, no man could beat Frank Taberski. Not even Greenleaf. And if not for a rule change, the legacy of the man they called The Snail might have been different.

Welcome back to Untold Stories. For this month's column I write about Taberski and his brief but glorious period of dominance. From September of 1916 until January of 1918 he was unbeatable. Taberski won the national championship during his first year as a professional - an unprecedented feat - and then emerged victorious in nine successive challenge matches. But he was undone by his own slowness. Fed up with Taberski's style of play, tournament promoters in 1918 began enforcing time limits. By speeding up the game, they slowed Taberski's rush to greatness - and ushered in the era of Greenleaf.

For students of pool history, Taberski and Greenleaf also offer fascinating parallels. Both became pros shortly after the modern form of straight pool became the championship game, both won multiple championships and both amassed records that remain standing today. But Greenleaf was the most famous drunk in pool, while Taberski was a Boy Scout, a man described by the press as "a fine example for young athletes who take up the green cloth game." Greenleaf would eventually be banned from competition.

For material in this month's column I've turned to early editions of Billiards Magazine, which can be found online at a site maintained by historian Charles Ursitti. I also contacted the public library in Sedalia, Missouri (the town where Taberski won his first national title) and poured through archival articles from the Chicago Tribune. I reviewed The Official Rules & Records Book from the Billiard Congress of America and the very entertaining Legends of Billiards booklet by George Fels. I also referred to the Encyclopedia of Pool, the excellent reference book by Mike Shamos, and consulted personally with both Shamos and Ursitti. Their expertise never ceases to amaze me.

So first let's dispense with the background. Taberski, who was born on March 15, 1889, exhibited very early in his life a seriousness of purpose beyond that of most other boys. He began shooting pool at age 13 in his hometown of Amsterdam, New York, and by age 16 was already the Central New York champion. Taberski also drove a milk cart during these early years, and then built upon that 3 a.m. -to-noon job to create his own grocery business. At age 22 Taberski sold his business for $10,000, a princely sum, and invested in poolrooms. By 1916 he owned three of them.

It was also in that year that Frank Taberski began making his name in the pool world. He placed only in the national championship, held February through March in Chicago - but still managed to do better than Greenleaf, who tied for fourth. (Taberski also beat Greenleaf 100-44 in head-to-head competition.) Emmett Blankenship placed first that year, but then lost the title in a challenge from Layton. Taberski then challenged Layton - an event that marked the beginning of The Snail?s remarkable run.

Next Page >

Top |

|