|

|

|

| HomeAbout Billiards DigestContact UsArchiveAll About PoolEquipmentOur AdvertisersLinks |

|

Browse Features

Tips & InstructionAsk Jeanette Lee Blogs/Columns Stroke of Genius 30 Over 30 Untold Stories Pool on TV Event Calendar Power Index |

Current Issue

Getting The Shaft Creativity and technology have combined to make shafts the most important part of a cue. How and when did this seismic shift take place?

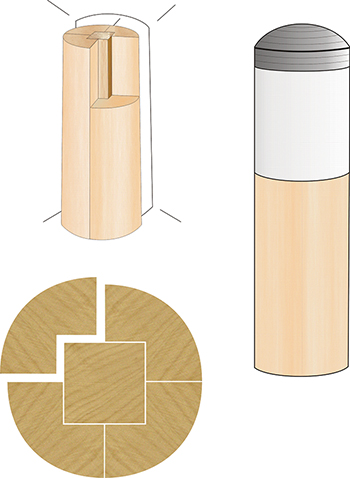

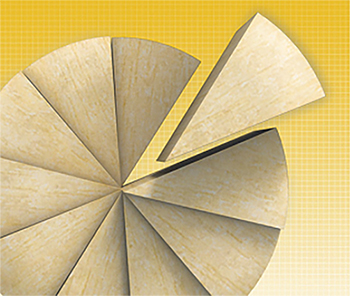

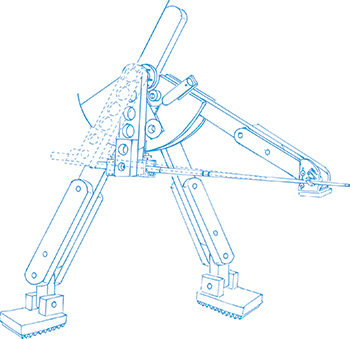

Bob Owen was a college student in the 1960s when he had the idea one day to build a pool cue shaft.By Keith Paradise Owen, who was a University of Oklahoma engineering student that also worked in the school's pool room, had an idea for a thin steel rod which would extend from the joint to the tip and was surrounded by four segments of maple. With help from a mutual acquaintance of Owen and his physics professor, he pieced together the prototype and took it to the pool room to try out. Much to his dismay, his super stiff creation had the exact opposite effect that he had hoped. "You could barely hit the object ball, it deflected the cue ball so far off path," Owen said. Seeing the results — or lack thereof, he tossed the shaft. Little did he know at the time that, some half century later, experimentation with shaft construction would become the rule rather than the exception in cue design. Back when Owen was pocketing balls and earning his degree at OU, pool players cared more about what was on the butt end of their cues than the shafts. The shaft was simply a piece of wood that came with the cue and held the tip. However, thanks to the creation, marketing and improvement of the low-deflection shaft, players are more likely today to be as particular about the top half of the cue as the bottom half. "It's definitely been a huge change for the billiards industry. It's created a whole new product line," said Kevin Engelke of online retailer PoolDawg.com. Deflection is the action which occurs when a cue tip strikes the cue ball using either inside or outside English. With the ball being struck off-center, the side spin coupled with the tip location on the face of the ball can cause the object to swerve, or deflect, off of its intended course. For example, using left-hand English could cause the cue ball to deflect to the right. Using the thicker, one-piece maple shafts common in previous decades, players would have to calculate a certain degree of cue ball deflection into their aim when lining up a shot. "A lot of people to this day are still confused about deflection," said Bob Meucci, owner and founder of Meucci Cues. "They think we're talking about the deflection of the shaft and not the cue ball. If the shaft does not flex and get out of the way, the cue ball will." Meucci could be considered one of the pioneers of deflection discussion, with 1976 sales literature discussing his theory on the peculiar cue ball movement and how his cues minimized the action. A competent player who made his first cue in 1963, the Mississippi manufacturer had been constructing cues and studying the unwanted cue ball movement for over several decades. After some experimentation, he concluded that cues constructed with stiffer shafts and ferrules, softer cue tips and stainless-steel joints result in a firmness that creates more deflection — and began building cues which would have an opposite effect. With the aid of a 1,000-frame-per-second Milliken camera, Meucci recorded a cue stick tip striking a cue ball and the cue can be seen pushing the ball off target in the photographs. During additional photographing he saw that the cue compresses all the way up to the top of the wrap in four different places — including at the forearm, joint and in the middle of the shaft. "What that did is load the shaft, or load the cue," Meucci said. "And you got more out of it than you put into it." Although players sometimes struggled to understand his deflection theories, that didn't stop many of them from using his product — with David Howard, Jim Rempe and Larry Hubbart using Meucci cues throughout the 1970s and 1980s. "Meucci did have the lowest deflecting cue out of all the cues, and the reason was that he had wood going all the way up through the ferrule and he had a lighter front end," said Allan McCarty, co-founder of Predator Cues and one of the creators of the original Predator 314 shaft. "So, his shafts played differently than most other cues."  Cue manufacturers have taken different approaches to multiple piece shafts, like Tiger's five-piece shaft. If Meucci was the cuemaker who created the term deflection, Predator was the manufacturer that helped popularize the terminology. Steve Titus and McCarty shared a love of two things, innovations and pool. The two had met in the early '90s at a women's pro tournament in Michigan and eventually joined together to work on a new type of cue shaft. First, Titus developed a robotic arm that could produce a consistent stroke in order to test how different cues reacted during different drills. Titus and McCarty then developed a shaft that was constructed of 10 pieces of laminated maple instead of a single, solid piece. The reasoning behind this was that wood is many times stiffer in one direction than the other, so the idea was to join multiple pieces for added consistency. "A lot of people thought that it made it stiffer. It didn't. It was within one percent of a traditional shaft," McCarty said. They would then reduce the front-end mass by hollowing out a section of the shaft near the tip. Although a subtle change, it reduced the weight of the cue by 30 percent, while only reducing shaft stiffness roughly 10 percent. This lower weight allowed the tip to get out of the way of the cue quicker. Additionally, they developed a narrower shaft diameter and sharpened the tip shape to a dime shape rather than the customary nickel after determining that the smaller tip point allowed the stick to strike the cue ball closer to the shaft's center. After a roughly 18-month research and development period, the Predator 314 shaft debuted in 1994. The product was the first low-deflection shaft to be marketed to the industry, promising to reduce the unintended cue ball action over other brands. Whether it was indifference to the research or inability to understand it, not everyone jumped on board with Predator's concepts in the beginning. "The people who were doubters, they didn't understand the low-end tip mass," Owen said. "People still think the cue ball moves straighter because the shaft is more flexible. I think it's simply players who don't understand the physics." One of Predator's early customers was Owen. "I bought a Predator shaft from Allan at the BCA Pool League tournament. His booth was right by the doors and I was fascinated by the technology," Owen said. "It was very interesting technology and I learned a lot from it," said Kazunori Miki, owner of Miki Company Limited, which builds the Mezz and Exceed cue lines. "I liked the technology as I talked a lot with Allan about it, so I looked into it to make our original shafts without infringing on their technology." Meanwhile, Meucci wasn't particularly fond of his new competitors, calling Predator's research "myths" and going as far as to bring his own mechanical deflection-testing machine — called the Myth Destroyer — to the 1999 Billiard Congress of America Expo in Orlando. "It was to debunk all of the myths that were out there that this particular brand of cue had 25 percent lower deflection than all others, which would include me," Meucci said. "Bob Meucci was pretty upset," said Titus. "It seemed like there was a rivalry there." Meucci also joined the performance shaft market in 1998 when he introduced his own Red Dot shaft and followed with the Black Dot shaft the following year. Equally important for slowly growing Predator, touring professionals, such as world champion Ralf Souquet, were starting to use the product. The German, who has been sponsored by the company since 2007, first tried the shafts when they came onto the market but wasn't satisfied with the initial product, mainly due to the company offering a thicker diameter than the 11.75 millimeters that he plays with. As the company modified and improved its low-deflection technology and offered smaller diameters, Souquet's opinion of the shafts shifted as well. "It took me about seven months to get used to it," Souquet said. "Now it's almost impossible to go back. You would have to go through a total makeover." As Predator's market share slowly increased over time, other manufacturers decided to get in on the action as well — each trying to not so much build a better mousetrap as a different kind. Much like Predator, Tony Kalamdaryan, Chief Executive Officer of Tiger Products, was just starting out in the billiards industry in the early 1990s, launching the Everest brand layered tip. As his tips grew in popularity, players began coming to him to have his tip installed onto their 314 shafts. Looking at the shaft's construction, Kalamdaryan looked at ways to make a shaft that would either be better or offer a different feel. "The first six or seven years in I wasn't even thinking about the shafts," Kalamdaryan said. "But then we started to ask ourselves if we could make a better shaft. That was the starting point." Rather than attaching multiple pieces of maple and turning the blank down into a shaft, Kalamdaryan decided on a five-piece construction for his shaft. Each blank begins with a long piece of rectangular wood which acts as the shaft's core, with four pieces of the laminated wood round the center piece. Roughly a dozen years after entering the billiard cue tip market, Tiger Products began making a laminated shaft. The company currently offers three different styles of performance shafts for players. Around the same time that Tiger launched its shaft, Owen found himself on a BCA Pool League team with a gentleman named Royce Bunnell. Much like Titus and McCarty, the two men discovered a mutual interest in cue construction and design. After pondering new methods to improve upon current shaft technology, they decided on blanks that would be constructed from six crescent-shaped pieces of laminated maple and tips attached with a unique wooden ferrule. Eleven years after the 314 was made available for sale, the first OB-1 shafts hit the market. "I want to make a better product and if I can't make a better product, I at least want to make it different," Owen said. The same year Owen and Bunnell entered the shaft market, longtime cue manufacturer McDermott Cues introduced its first-ever high-performance shaft — the i-Shaft — which features a carbon fiber rod inserted inside of a solid piece of maple to give customers the low-deflection technology they desired with the traditional look of wood. "We had seen the popularity and demand for the high-performance shaft, so we wanted to make something unique and something that stayed true to our tradition," said Derek Blaguski, Creative and Marketing Director at McDermott. Shortly after McCarty and Titus's three 20-year patents for the technology developed on the original 314 shaft expired, nearly two dozen cue manufacturers had a low-deflection product on the market. "Once other manufacturers were able to enter the market with their own versions, that was the kick off point for everyone jumping into the pool," said Eric Weber, co-owner of Colorado-based CueStix International, which manufactures and markets roughly a dozen of its own brands and distributes other manufacturers as well. Weber's own Katana brand offers the Katana1 and Katana2, both of which are 10-piece spliced laminated low-deflection shafts. The Katana shafts also come in various joint sizes for different cue styles. The new choices in low-deflection technology afforded players the opportunity to customize their shafts, offering a variety of diameters, lengths and even tip types. It was a sweeping change from the "off the rack" shaft offerings of the past. Weber, who said the impetus behind opening CueStix was to give players more variety, said that a player looking for customization of shafts was limited to what manufacturers were making three decades ago. And the options that were offered were pretty limited. "Unless you bought it directly from the manufacturer or knew someone in your town, you were getting a 13mm shaft because that's all that was available," he said. Weber has seen the popularity of the performance shafts slowly grow over time, with a major explosion taking place in the last five years. However, he is not convinced the additional offering has materialized in added revenue from a wholesale standpoint.  Carbon fiber is the latest trend in shaft technology. Shown here, the new Cuetec Cynergy. Whether it makes money or not, Weber has to have low-deflection shafts in stock for his customers. With many manufacturers offering one shaft model in various lengths and widths, this means an entire of section of his warehouse is now devoted to shafts. "All of these companies have variation after variation and, as a wholesaler, I have to carry it," Weber said. "It's a lot more difficult. For me, it's more expensive. It's given a significant amount of options to the end user but it doesn't necessarily add dollars from the business side." As technological advances in other sports like golf and tennis slowly make their way into billiards, the cuemaking arms race is now entering the carbon fiber arena. Much like a quarter century ago, the race started when Predator placed a product on the market: the Revo shaft. The black, ferrule-less shaft was introduced in 2016 in two diameter sizes and created a buzz almost instantly. When McCarty was looking to create momentum for his 314 shafts, he would give them to well-known regional and national professionals, knowing they would talk the product up after using it. Twenty-five years later, Predator used the same approach with its carbon fiber shafts, placing it in the hands of worldwide professionals like Darren Appleton — who initially was one of the shaft's earliest detractors. He considered the new equipment to be a gimmick and actually laughed when he traveled to Predator co-owner Paul Costain's shop and saw the shaft for the first time. That was until he began to strike balls. Shortly thereafter, Appleton committed to competing with the shaft during the 2017 season. Fellow professionals Chris Melling, Eklent Kaci of Albania, and talented young German Joshua Filler also switched from their wooden shafts to carbon fiber within the past two years. "People think it's a gimmick, it's a marketing ploy, but you're not going to play with it if it's your livelihood and you're not comfortable with it," Appleton rationalized. When Predator introduced the first 314 it took a fellow competitor four years to introduce its own version of the product. Cuemakers have adapted to the carbon fiber trend much faster, with Cuetec introducing the Cynergy 15K carbon fiber shaft in the middle of last year. Much like competitor Predator, Cuetec, launched in China by Jones Chang 30 years ago, has a top professional on its staff who has also recently shifted to carbon fiber technology. American champion Shane van Boening debuted his Cynergy shaft eight months ago after using the same R360 shaft for the past eight years. The five-time U.S. Open 9-Ball Champion had played with a fellow competitor's Revo shaft a couple of years earlier and struggled with aim due to the sleek, monochrome design. Last year, while Van Boening was in China for the World Cup of Pool, he met with representatives from Cuetec and exclusive U.S. distributor Imperial International. Knowing that the company was working on a carbon fiber shaft of its own, Van Boening intimated that he needed a white ferrule on the end to help with aim and sighting. Two weeks later, the ferruled shaft arrived at Van Boening's home and he's been using it ever since — placing fifth at the International 9-Ball Open and third at the World 9-Ball Championships. "Everything played the same, it just had a better touch and a better feel," said Van Boening. "The hit, feel and feedback that we've been able to achieve with the 15K is superb. It feels more like a wood shaft that any other product on the market," contends Kyle Nolan, Cuetec Brand and Communications Manager, who added that Cuetec's transition into synthetic shafts was seamless since its parent company had been making carbon fiber automobile parts and sporting goods for years. Like any new technology, there are advantages and disadvantages to carbon fiber shafts. Professionals like Appleton and Van Boening insist the cue ball action with carbon fiber shafts is effortless. Players that don't carry a big game but are looking for pragmatic reasons find an advantage in the material's warp-resistant and dent proof qualities. The two biggest disadvantages to the carbon fiber shaft are that it isn't wood and won't have the same feel or characteristics. Lastly, there's the cost — with the Revo being advertised for $499 and Cynergy retailing for $449. The price, however, has hardly curtailed demand, with both manufacturers insisting that they are struggling to keep up with orders. According to Predator Vice President Philippe Singer, the company has increased the number of employees manufacturing the shafts from three initially to 20 and has moved production operations three times since the product's launch in order to try and keep up with demand. The production increase has allowed them to catch up on orders for the 12.9mm model while the 12.4mm version still maintains a lengthy waitlist. Although he was not able to provide specific statistics, Nolan stated that Cuetec has sold thousands of its Cynergy 15K shaft and is currently working its way through backorders as well. "The market's response has been outstanding and we're increasing capacity to keep up with demand," he said.  Spliced construction, like Predator's 314, eliminate grain directionality. Ask a handful of cuemakers and each one will tell you that they've been experimenting with carbon fiber shaft technology for at least a decade, but have struggled to find consistency with the material. McDermott's Blaguski said the company started developing carbon fiber shafts almost two decades ago but said there was little interest from customers so the products were tabled. "More than 10 years ago we started experimenting with composite materials, as we already had a masse shaft with composite material and we use carbon pipe as the core materials for the EX Pro shaft," said Miki. "So, carbon materials is nothing new, really. It's just that the marketing strategy of Predator made a big buzz, I believe." Because of that early experimentation, more cue manufacturers will be bringing carbon fiber shafts onto the market this year — with Jacoby, Meucci, Pechauer and Mezz each releasing new products in the months to come. Meucci currently has 800 shafts on order and anticipates he will sell around 10,000 units in his first year. The product, which carries a manufacturer's suggested retail price of $399, will come in five different diameters and will be able to accommodate most joint sizes. Miki said that he also currently has thousands of orders for his Ignite 12.2mm carbon shaft, which will take some time to work through since he operates a smaller shop and is not able to churn out big numbers of product quickly. CueStix currently distributes the Predator and Cuetec carbon fiber shafts and has placed orders for the forthcoming Jacoby, Meucci and Mezz models. "Demand is intense and backorders are long and deep," Weber said. "I don't even know in 30 years if I can remember another scenario where there has been a product class or innovation that the manufacturers haven't been able to keep up. It's very different for us to get on the phone and say, ‘I'm sorry. I'll add you to the list. We'll call you if it shows up in a few months.'" Meanwhile, representatives from Tiger, McDermott, OB and Cue and Case, which manufacture Lucasi and Players brand cues, stated their companies are currently developing a carbon fiber shaft but that there currently isn't a timetable for any product launch. With a handful of shafts already on the market, manufacturers are seeking to develop a product that will differentiate itself from the items already available. "We don't want to put something out there that is a carbon copy," said McDermott's Blaguski. "When we have something that is unique and what we feel is an improvement over what is out there we will bring it to market." Meanwhile, Owen, who obviously is no stranger to evolving cue shaft technology, wonders if the synthetic material shafts might someday be looked at as a passing, fashionable trend. "The benefits of carbon fiber are probably miniscule and if the people don't start charging a lot less it will probably go away," he said. "I think it's a fad now and I think a lot of people can't distinguish the difference. I think that's also true of low-deflection shafts." Conversely, a few manufacturers worry about the dwindling quantity of quality maple with which to construct shafts and feel that eventually the amount of wooden shafts and carbon fiber shafts sold will be about equal. "Getting straight, tight grain maple has always been an issue for the industry," said Costain, who helped develop the Revo. "Keeping a wooden shaft straight, clean and dent-free will remain a challenge for a majority of players." While the carbon fiber market segment continues to expand, a few professionals recently have opted to go back to older technology. Filler won the World 9-Ball Championships in Qatar in December using his old Predator Z-3 because he liked the taper. "The Revo is an unbelievably good shaft and I had really good achievements with it but I like to try new things," he said. "I'm trying new Predator products soon and will probably be back with a new Revo." Another player who has gone back to a wooden performance shaft is Appleton, who is training to play a full 2019 schedule after scaling back over the past two years to tend to his ailing mother and operate the World Pool Series. The Billiard Congress of America Hall of Famer considers touch and feel to be two integral attributes of his game and thinks a maple low-deflection shaft currently benefits his game more.  Carbon fiber, which comes in spools like those in Cuetec's China plant, is the latest shaft rage. "I haven't ruled it out, but I think the best thing for me is to play with wood at this point in time," Appleton said. Although low-deflection and performance technology have changed how many play the game and how almost every cuemaker and retailer sells equipment, not everyone is a believer. "I wouldn't say that everyone has completely bought in either. There are some people out there who think that low-deflection technology isn't a requirement," said Weber. "So, while its overwhelmed the industry, there is still a faction of people who don't think it's a requirement or believe it." One member of that faction is 1996 U.S. Open 9-Ball Champion Rodney Morris. The Billiard Congress of America Hall of Famer gave low-deflection technology a try earlier in this century and committed to using a Predator shaft in his run to a top-four finish at the 2002 U.S. Open, but struggled to find his touch with the equipment. Morris, who is now retired from professional pool, ultimately went back to a more traditional shaft construction, believing that his ability to implement inside and outside English was more consistent with good, old fashioned maple. "Pool players are constantly changing. We're always looking for something," Morris said. "You'll get into a groove with a shaft and then fall into a funk, pull out another shaft, start using that and get into a groove with that one. Meanwhile, I hated that shaft a year-and-a-half ago." The Mother of Invention A pair of "egghead" pool players helped create a market that, at first, didn't appear necessary.

Steve Titus doesn't remember all of the details anymore. Twenty-five years has a tendency to cloud one's memory. But he does remember the reaction when he and partner Allan McCarty were finalizing the design on the original Predator 314 shaft. "Once we realized what we had, we were just giddy," Titus said. "We just thought we were going to be overnight millionaires." It didn't happen overnight, but that shaft company that started in a Michigan workshop has grown to be one of the biggest cue manufacturers in the world. This year marks the 25th anniversary of Predator coming to market with its original shaft, and it is easy to argue that the cue making industry hasn't been the same since. At the time of its creation, manufacturers did not offer a shaft specifically designed to reduce deflection. A quarter of a century later, the technology is pretty much offered industrywide. "I have to give it to Predator. Today everybody knows it is the shaft that makes or breaks the cue," said Tony Kalamdaryan of Tiger Products. Titus and McCarty first met at a women's billiards tournament in the early 1990s. Both were frequent players who had dabbled in the billiards business. Titus had experimented with some cuemaking and was kicking around the idea of co-owning a poolroom when he met his future partner. McCarty owned a billiards product company that, at the time, sold a shaft burnisher, talcum powder dispenser and an alcohol wipe.  McCarty and partner Titus unveiled the 314 shaft in 1994. "The problem was, the burnisher never wore out, the talc took about three years to go through and the alcohol pad never caught on," McCarty said. "So, there was no repeat business." Both had an interest in building a better performing cue. The idea was especially of interest to McCarty after he lost a three-cushion match due to an equipment failure. Given 3-to-1 odds, with his opponent betting $300 to McCarty's $100, he took a brief lead midway through a race-to-100. Unfortunately, the tip came off his shaft in the later stages of the match. He switched to a backup shaft and struggled to make contact with the balls, ultimately losing. "And I just walked away wondering why these two shafts played so differently," McCarty recalled. McCarty's plan was to build a robot which could create a consistent, repetitive stroke in order to test out different styles and constructions of cues. Once Titus completed the robot — later named "Iron Willie" — the two men began applying spin to the cue ball with the robot in order to check deflection, or "squirt" as it was sometimes called. Once initial research was completed, they began the task of experimenting with construction methods which reduced the unwanted cue ball movement. "It was just a dream for two egghead pool players to have this machine that could answer all these questions that people had debated for years and years," McCarty said. "It really led us to break all of the theories on the performance dynamic of the cue." The first thing they noticed from experimenting with the robot was that deflection was reduced between 5-10 percent when the tip's shape was reduced from nickel shape to that of a dime, namely because the sharper tip hit closer to the center of the shaft. It also didn't hurt the business model that Titus had previously been tinkering with shaft designs and had constructed a six-piece spliced shaft. McCarty was immediately taken by the look of the wood, but tried to hit some balls with it and struggled with the amount of deflection the shaft contained. As they tinkered with Titus's creation, they determined that when a hole was bored into the shaft at the tip, it reduced rebound stiffness by 10 percent but decreased front-end weight by 30 percent. It also reduced deflection. To reaffirm the theory, Titus left the office one day for a couple of hours, returned with lead tape and attached a half-ounce of tape to the ferrule and watched as the shaft deflected 30-40 percent more. All in all, it took about a year and a half to bring the completed product to market. Originally named Clawson Custom Cues, since the company was based in Clawson, Mich., the cue company was renamed Predator shortly after Jim Lucas of Cue and Case Sales came aboard as a partner. Predator would make the blanks for the shafts, then ship them to Ernie Chen of Falcon Cues in Toronto to be turned down into partially finished shafts. Chen would then ship the products back to Florida to be finished off with the technology within the ferrule and tip. With their new invention in tow, Titus and McCarty started hitting tournaments and trade shows with those first 314's in 1994. In a game that is steeped with tradition, both in terms of rules as well as equipment construction, the industry wasn't exactly quick to embrace the two men's analysis. "There was a new phrase coined, ‘deflection, meflection,'" said McCarty. "Everyone made fun of deflection." McCarty was undeterred. While Predator used traditional methods of promotion to spread the story of the shaft, he also networked with professionals. McCarty would give the competitors a couple of shafts to try out and use, knowing they'd eventually talk to fellow players about the product if they liked it. McCarty not only handed out shafts to nationally known players like Tony Robles but also regional heavyweights, like as Ohio's Bucky Bell. Eventually word spread and Predator soon found itself having to catch up with demand.  Iron Willie As additional investors moved into the company, Titus left in 2000 but continued to work with manufacturer on product development. He helped in the creation of the 314-2 shaft, the BK2 break cue as well as jump cues. Titus started working with carbon fiber friction rod and golf shaft blanks around 2000 with the intention of using the material to construct a jump cue. He ultimately scrapped the idea, but sees similarities between his early efforts and the new Revo shaft. "I still have some prototypes that we made in '03 and it looks exactly like the Revo. It's identical," he said, laughing. "It's just it took 15 years to bring it to market." Roughly eight years after Titus's departure, McCarty sold his share of the company, retiring in the Jacksonville area where he can be found playing the occasional round of golf or one-pocket. While McCarty had to network and develop rapport with professionals to try out his shaft 25 years ago, today some of the world's top male and female players compete with the company's equipment. "I'm constantly amazed by it. That I had a part in it," Titus said.

|

|

Since 1978, Billiards Digest magazine has been the pool world’s best source for news, tournament coverage, player profiles, bold editorials, and advice on how to play pool. Our instructors include superstars Nick Varner and Jeanette Lee. Every issue features the pool accessories and equipment you love — pool cues, pool tables, instruction aids and more. Columnists Mike Shamos and R.A. Dyer examine legends like Willie Mosconi and Minnesota Fats, and dig deep into the histories of pool games like 8-ball, 9-ball and straight pool.

Copyright © 1997 - 2025 Billiards Digest

All Rights Reserved

Luby Publishing, Inc.

310 Busse Highway PBM #319 | Park Ridge, IL 60068

Phone: 312-341-1110 | Fax: 312-341-1469