|

|

|

| HomeAbout Billiards DigestContact UsArchiveAll About PoolEquipmentOur AdvertisersLinks |

|

Browse Features

Tips & InstructionAsk Jeanette Lee Blogs/Columns Stroke of Genius 30 Over 30 Untold Stories Pool on TV Event Calendar Power Index |

Current Issue

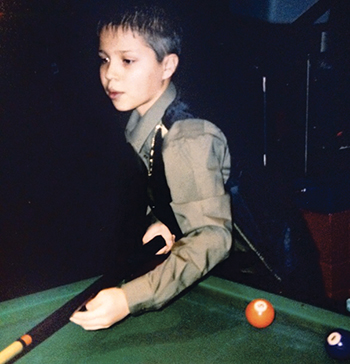

Drastic Measures John Morra's decision was simple: Learn to play left—handed or give up pool. The road back to the top, however, has been anything but simple. By Peter Warren John Morra can't remember the date specifically or the exact tournament he had just played in but he can vividly remember what he was feeling when he said enough was enough. It was early 2018. Morra was 28 years old. He had been playing world class—level pool for nearly a decade. But the Toronto native was burned out. For years, Morra had been dealing with pain in the trapezius muscle on the right side of neck and down to his shoulder. The pain had started small but over the years it grew, and it persisted. His mood deteriorated because he was always in pain. His play suffered because he was always in pain. His love of the sport evaporated like a pond in a desert because he was always in pain. The thought of quitting and leaving the tour had been lingering in his mind for years, he said. But driving back from this forgotten tournament, he said he was done. The decision was the right one but not a happy one. There was no cathartic release letting go of his pool life. He didn't reflect and reminisce about the matches won and friends made along the way. He didn't feel any weight off his shoulders knowing the pain in his right one would soon subside. No, all John Morra felt was sadness. “I think it was like the day or the day after — I don't know — but it was right when I knew I was going to quit, like I made the decision, I was just in my room bawling my eyes out. I was a mess,” Morra remembers. That moment, one of emotion and sadness, wasn't the end of the road for Morra. It was just the nadir of his Phoenix—like career. Less than a year later, Morra was back on the tour competing and finding his groove again. Four—plus years later, he is in as good of a place as he has ever been as a player. He's confident on the floor. He's healthy off it. And he feels he is on the verge of the major trophies that have eluded him for over a decade. It's all thanks to one major change: making the drastic, unprecedented decision to go from a right—handed shooter to a left—handed one.  (Photo by Erwin Dionisio) John Morra is one of those athletes born to play their sport. The son of two professional pool players — Mario Morra and Anita McMahon — he took to the game very quickly as a child. He started winning big—time tournaments around Toronto when he was 10 years old. At 14, he won the Billiard Congress of America Junior National Championship in the 18—and—under division and then finished third at the world championships. When he emerged on the professional scene about a decade ago, Morra was a player oozing with potential who was able to tap into a lot of it. Jeremy Jones put him in the top 15 in the world at his peak. He won some impressive tournaments, including the 2012 Derby City Classic in the Banks Division at age 22. His biggest win came at the 2016 Players Championship, when he toppled Shane Van Boening to claim his biggest pro title. But like a young child unable to reach Grandma's cookie jar on the top shelf, Morra was never able to break through with the consistency to reach the pinnacle of the sport. As Morra struggled through close—but—no—cigar tournaments, the pain in his neck began to intensify. “It was just because I played a lot,” John Morra said. “I started feeling it when I was in my early 20s and then in my mid 20s, it got worse.” Morra was a right—handed shooter and a left—eye dominant player. As his career progressed, his cue veered towards to his left eye when lining up his shot. He would then torque his right arm inward to the left to line up the shot. That resulted in him stressing the trapezius muscle in his neck and right shoulder as well as hitting his body on the follow through. In isolation, the motion isn't one that would cause significant pain. But after years and years of doing the stroke, the discomfort sharpened and lasted longer. “It was hard watching him because he was in pain,” his father Mario recalls. He tried many ways to try and subdue the pain over the years: stretching, massage, chiropractor. To this day, he will still get in the shower and have hot water run down his neck for 10 or 15 minutes. “I was in a bad mind frame mostly all the time,” Morra said. “It just affected my mood. It affected my whole nature, my whole mentality surrounding the game and my life too. When you're always in pain, you're not enjoying life in general.”  Morra, here with fellow Canadian Alex Pagulayan at the World Cup of Pool, struggled with pain as a right-hander. (Photo By JP Parmentier) When Morra left the world of pool, he had his sights set on being a DJ. He was — and still is — a big fan of house music. His hometown of Toronto has one of the best house music scenes in the world. The new challenge of DJing excited Morra but he also was realistic about the difficulties of the profession. He knew it would take some time to actually earn good money. As a result, he returned to the pool halls. He gave lessons and started playing again — but with his left hand. Morra had messed around shooting opposite handed for fun and was proficient. “I didn't want to work a regular job to support myself,” Morra said. “I've never worked so it was like if I can still play to earn my living then I'll do that. I just won't compete professionally and travel anymore.” But pool was his true love and being around the game and seeing the progress he was making inserted some confidence in him. He was winning locally, why couldn't he win internationally shooting lefty? “I don't want to sound cocky about it but it's like a special kind of belief just in yourself,” Morra said. “Only you know it. You can't convince anybody because they just won't understand, but you know it. I just really believed it. I knew I had the work ethic. I always had the work ethic right—handed. I knew I just put the work in. I have to be able to succeed at it, like there's no other way that it's gonna work.” With his girlfriend at the time, Morra stopped DJimg and moved down to McAllen, Texas, in the Rio Grande Valley. McAllen, located right near the US—Mexico border and about two hours and 30 minutes south of Corpus Christi, is not a pool town. His friend had the only Diamond table in the city. It was there where Morra dedicated himself to playing left—handed. Morra is a naturally talented pool player with a brilliant mind for the game. He started doing the exact same practice sessions he did when he was playing right—handed. Discovering his stance and positioning came fairly easy. Discovering his stroke took time. Even now, four years after he first started really experimenting, Morra said he can lose the stroke quickly if he takes a few days off. He didn't do anything crazy to find his stroke. The most important thing he said he did was practicing his strokes on the line between the cloth and rail. “That's basically the only drill I've done in four years,” Morra said. He's favorite training activity was playing races 11 against the ghost. “I was building it up inside me,” Morra said. “I was like, nobody knows this, but I am going to come back to the game professionally as a left—handed player. It was exciting. Only I knew it, and people around me were like, ‘You're really never gonna play right—handed again?' I was like, no. People just didn't understand how much I believed in it. Because it's such a crazy thing. It's really unheard of.” Morra said part of the reason for his quick development as a left—handed player was his previous experience as a right—handed player. He had been around the game his whole life. He had succeeded and failed at the game's highest level. He had learned from some of the world's best. That made his development as a lefty occur even quicker. When someone young is learning to play, they are almost always learning as much about the game mentally as they do physically. Morra was completely opposite. No one is ever done learning, but he entered with an elite IQ. He knew what he wanted to do, and he knew how to accomplish it. There are a lot of similarities between Morra's right and lefty stroke. “Eight out of 10 shots, it doesn't seem like he changes much from left to right,” Team USA captain and elite instructor Jones said. “His form looks pretty similar. You can see it's a little more mechanical lefty, it doesn't have quite the rhythm of the righty. But very similar in styles, very similar on the screen.” His father sees little difference in how he looks now than before. “He still stays down on the cue. He still delivers a stroke the same way,” Mario Morra said. “He's had that stroke for the last 15 years.” Morra does not do every shot left—handed. He can't generate enough power lefty on the break, so he still does that righty. He will also switch over to his right when that gives him a better angle on the pool table or needs to really hit it hard. But the majority of his shots are left—handed. After a few dedicated months of training, Morra believed he was ready to return to the tour. So, in the fall of 2018, he did. “I wasn't in pain anymore,” Morra said. “After years of putting my body through pain, I finally was just able to relax. Give my neck and my shoulder and everything a break. It was just so relieving to not be in pain. But it sucked because I wasn't competing, I wasn't traveling, and I didn't know what I was going to do. It was a good time to refresh and get myself re—energized and just a massive weight off my shoulders — literally.” Some of the most historic stories in all of sports are heroic tales of athletes and teams beating incredible odds on their way to remarkable comebacks. But what Morra is doing is unprecedented. That doesn't mean similar feats haven't been tried in other sports recently. Switch hitters in baseball and softball are the most obvious example, but they don't start switching hitting when they reach the majors — that process starts well before. There have also been occasional switch pitchers, most recently Pat Venditte, who had been throwing with both hands since his childhood. Throughout the history of golf, there have been some players who are switch putters. Notah Begay III is the most recent famous example. During his college career at Stanford — where he was a three—time All—American — Begay started experimenting with switch putting as a way to always have a favorable break on his long putts. He shot a 62 in the third round of the 1994 NCAA Championships, the lowest score in history, as the Cardinal went on to win the title. He continued switch putting after he turned pro, winning four PGA Tour events and ranking as high as 19th in the world. While Morra is technically a switch shooter, his situation is very different than all of them. Those players all switch hands to gain some theoretical advantage. That's not the case with Morra. There's no inherent advantage to shooting right or left—handed. None of the other athletes made those changes after reaching the highest level of the sport, either. Nobody learns to switch hit when they've played nearly a decade in the majors. Nobody learns to switch putt after winning multiple professional tournaments. Nobody plays quarterback in the NFL throwing right—handed and then changes to throw lefty. The closest sports comparison to Morra, where an athlete switches dominant hands in the middle of their professional career, is former basketball player Landry Fields. Landry Fields was a sharpshooting wing for the New York Knicks during the team's recent high point one decade ago. A key role player and starter for the team alongside Jeremy Lin and Carmelo Anthony, Fields had a smooth right—handed jumper that helped him land a three—year, $26—million contract with the Toronto Raptors. But soon after signing his contract, Fields started dealing with a mysterious nerve injury in his right arm. It derailed his career. His shooting dropped off. Doctors couldn't agree on what the actual issue was, and to this day there's no real definitive answer. During the final year of his contract, he tried to learn how to shoot lefty. It didn't work. “That right hand still had its way to a certain degree,” Fields told “The Athletic” in 2020. “I got to a point where I thought it was pretty good. I'd have stretches where it was great and then stretches where it just wouldn't go away, and I couldn't do anything.” Fields was out of the NBA when his contract ended. He was 26 years old. Morra has been competing at the highest level for four years with no signs of stopping.  A child prodigy, Morra was winning at 10. Many players mess around with their opposite hand, including Morra himself before he transitioned to left—handed full—time. But very few have done so at the highest level in major events. Legendary player Cecil Tugwell — who went from right to left in the 1970s because of a car accident— is probably the most famous example of pool player switching his stroke full—time. Tugwell was still regarded as an excellent player after switching hands. “He was before my time, so I never really got to see him play righty but from what I hear, it's pretty incredible what he could do switching hands,” Jones said. Morra has joined Tugwell in the now exclusive club of players who switch hands and succeeded. But when Morra returned to the pool scene later in the year, people were skeptical. They thought it was a gimmick. “It was really cool to be back and kind of felt odd at the same time,” Morra said. “They didn't take me that seriously with it. A lot of people felt like is he trying to get attention from this? Is this like a cry for attention or something? Is he trying to show off? People didn't really understand my problem.” Tugwell's transition had been nearly a half century prior and there was a much more easily digestible reason for the switch. There is a much more visual element to understanding changing your style due to a car accident he was in. “The car hit me on the left, but almost everything on my right had twice the damage of the left,” Tugwell told onepocket.org in 2008. “I've got a lot of scars on my hands and body, but most of the damage was done on my right side for some reason.” But even beyond trying to understand his reasoning for the decision, people just couldn't see a return path to where he once was pre—retirement. “When I first heard about it, even first saw it, I thought it was kind of — I don't think novelty is the right word,” Jones said, “but I didn't see it as being a realistic thing for him to be able to compete at the level that he did before. Boy was I wrong.”  Morra nabbed his biggest pro title in 2016, beating Shane Van Boening to win the Players Championship. It didn't happen all at once, but Morra kept getting better and better. He is a naturally hard—working player. “He is very, very determined. It's just determination, sheer love of the game. He just wants to play,” Mario Morra said. That mindset helped keep John going during the early days when he wasn't winning much and missing a lot of shots. The only thing that was going to change people's minds would be for them to see Morra compete and win with their own eyes. But slowly Morra started picking up victories — and not just over lower—ranked opponents. He started defeating some of the best in the world, and people start taking him more seriously. Morra didn't need to prove himself of much, but he did have to prove to others how good he is lefty. He said he has now beat everyone he ever beat righty with his left hand. Morra posted a solid ninth—place finish in the 200—plus player 2021 U.S. Open Pool Championship, surviving five elimination matches. In 2022, Morra has posted a fifth—place finish at Turning Stone, fourth in the Derby City Banks division and 17th in both the World Pool Championship and UK Open. Still, Jones and Mario both say Morra is not as good as he was right—handed, which makes sense due to the lack of power generated from his left hand. But they both add that he is really, really close to where he was in his right—handed prime. Jones puts him in that top 25—40 range. “He's messing with the best in the world and still trying to be the best in the world,” Jones said. “I don't know what the number is: 99 out of 100 just would have gone the other direction, maybe stayed in pool doing whatever they can do, but not trying to totally overhaul your game.” Rebuilding his stroke wasn't the only thing Morra had to rebuild in the wake of ending of his right—handed career. “I always loved the game,” Morra said. “I always had great appreciation for it. It's only when I started feeling the pain and just the traveling, the losing, the ups and downs, that's the part I didn't know how to deal with. That's the part that was hard. Just quitting and then coming back to it, it really gave me the appreciation that I had when I was young, getting good at the game, when the game was so much fun.”  Despite the dramatic change, Morra has returned to world-class caliber, with top-10 finishes in several major international events. (Photo by Erwin Dionisio) That love, which Morra says for better or worse is the deepest in his life, has been renewed. Morra is an intense player around the pool table. That hasn't changed. But his general mood is much better during the game. The players who were rightly skeptical of him when he first returned aren't skeptical anymore. “We're all super impressed and it never goes away,” Jones said. “Every time you see him play it just reminds you of all the hard work.” He is happier outside of the sport, too. Morra, who has dealt with addiction during his career, has been sober for over a year. It's an accomplishment he considers bigger than any victory he's ever achieved in pool. Morra is extremely grateful for where he is in his life. “It was so hard in my 20s as the pain got worse, the drugs, the alcohol, everything was going wrong,” Morra said. “My life was just like in shambles. I never thought I'd be able to be in this position where this is the first time I know I'm gonna achieve those things I've always wanted to achieve. I really believe it.” That confidence makes him feel like he is on the brink of what he has always wanted, the white whales of the first 33 years of his life: major tournament trophies. Such a win would be the fairy tale ending to the Hollywood script of his life. Morra clearly believes he is on the precipice of such a win. Jones thinks he will be able to get it done. Mario wants to see that for his son so badly. “I just hope he does it,” Mario Morra said. “I hope he does it for himself.”

|

|

Since 1978, Billiards Digest magazine has been the pool world’s best source for news, tournament coverage, player profiles, bold editorials, and advice on how to play pool. Our instructors include superstars Nick Varner and Jeanette Lee. Every issue features the pool accessories and equipment you love — pool cues, pool tables, instruction aids and more. Columnists Mike Shamos and R.A. Dyer examine legends like Willie Mosconi and Minnesota Fats, and dig deep into the histories of pool games like 8-ball, 9-ball and straight pool.

Copyright © 1997 - 2025 Billiards Digest

All Rights Reserved

Luby Publishing, Inc.

310 Busse Highway PBM #319 | Park Ridge, IL 60068

Phone: 312-341-1110 | Fax: 312-341-1469